Foundational Research for Uber Accessibility

An end-to-end project exploring the transportation needs and barriers for people with visual disabilities.

The Problem

Transportation is a major barrier for people with visual disabilities.

- What factors influence the decision-making of blind and low-vision people when going somewhere?

- What are the barriers for existing transportation options?

- How do rideshare options like Uber help (or hinder) the transportation experiences of blind and low-vision people?

The Research

A multi-phase, mixed-methods research project to understand the many facets of the problem.

In order to understand the variety of experiences and needs of blind and low-vision riders, I adapted my research methods to participants needs.

- Interviews with Uber drivers

- Heuristic evaluation of the Uber app's accessibility

- Semi-structured interviews with blind and low-vision people in the Bay Area

- Ride-alongs with blind and low-vision riders in a variety of transportation methods

- Co-creation of soundscape recordings to help me understand how sound helps blind and low-vision people to navigate

Inclusive Research Recruiting

Recruiting disabled participants for research comes with certain challenges. It is best practice to never ask for a diagnosis unless it is critical to the research. So sending a screener to a general population asking for blind participants was an absolute no-go.

However, I sidestepped this challenge by partnering with several organizations in the Bay Area that serve individuals with visual disabilities. Because they explicitly identify their clientele as "blind," it was possible to create a straightforward screener to recruit participants.

Interviews and Ride-alongs

I conducted interviews in several stages. Initially, I met with five Uber drivers who had recently driven a blind passenger. They provided a key insight: they wanted to help as best they could, but they did not know how.

Once I began interviewing blind people about their transportation needs and habits, it became clear that the project would expand in several directions. I rode with participants in Ubers, city buses, paratransit vans, and even walked a couple times (according to the participant's preference). I learned about the range of concerns and barriers blind people encounter in their transportation, from extreme cost sensitivity to hostility from taxi and rideshare drivers. For regular rideshare users, these challenges were compounded by inaccessible apps that added to the anxiety of finding a car as a blind person in a public space. There were many issues to address!

Participatory Phonography

To supplement the ride-alongs and semi-structured interviews, I employed a research method I developed specifically for this project, which I called "participatory phonography." My goal with this method was to learn how blind people use sound to navigate, and then to think about how that knowledge could be used to create a more inclusive multi-sensory experience.

The method was inherently participatory: I asked participants to choose a location of interest or significance to them. We went to that place and then collaboratively used my recording equipment (a Tascam recorder and a few microphones) to capture the key sounds of the location. Then I talked through the soundscapes with the participants, noting what they focused on and what it meant to them. It was, in essence, a way of "hearing through their ears."

Heuristic Accessibility Assessment

While not a proper accessibility audit, my heuristic evaluation of Uber's app laid important groundwork for subsequent systematic auditing and remediation of accessibility flaws.

I established usability criteria for Uber's rider app and then tested it with VoiceOver (Apple's screen reader software) to determine if someone who could not see the screen could use the app's features. The criteria included:

- Can the user access every feature on the screen?

- Is the focus order logical and meaningful?

- Do the VoiceOver readouds accurately describe the content or function of each element?

- Are there any focus "traps" (elements that a user cannot swipe away from)?

Findings, Analysis, and Recommendations

"I understand, you know. [Uber is] not designed for people who have a vision problem."

Without exception, everyone that I interviewed felt excluded and discriminated against—not only by Uber, but by the inaccessible transportation systems they were forced to use. As Marie, a participant with low vision, told me, Uber is just not designed for someone like her. My recommendations aimed to create inclusive designs that would allow people to use Uber regardless of their individual abilities.

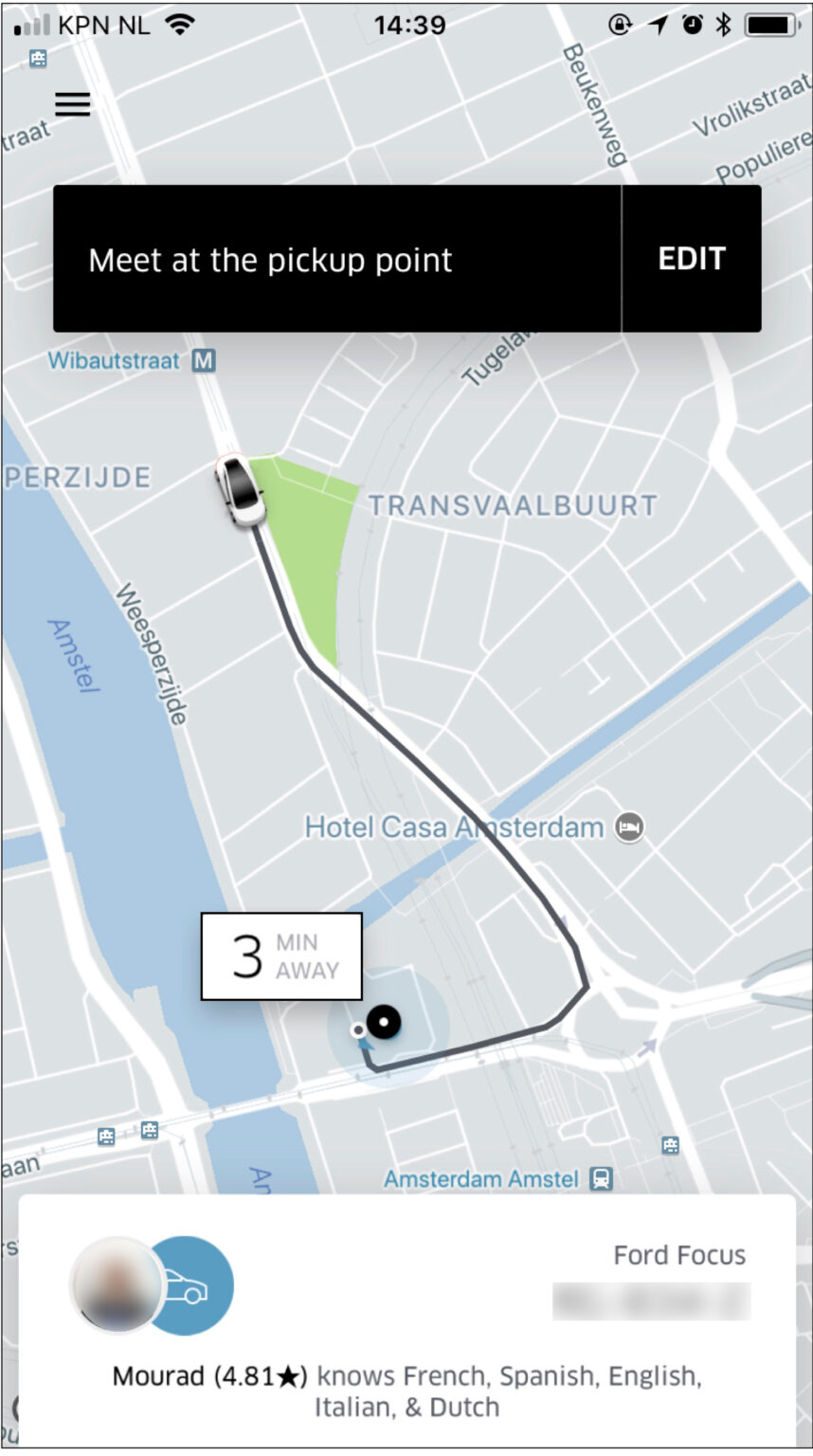

Insight: The Uber app does not provide useful information to blind riders

Participants consistently indicated that they needed different information to use the Uber app effectively. The app provides information that is only useful for sighted people (make and color of car, picture of driver, license plate). Users wanted to know distance and direction of arrival in addition to the estimated time of arrival.

Recommendation: Modify VoiceOver readouts to include distance and direction This solution is inclusive because it does not require a redesign of the visual elements, only the addition of information for non-visual users.

Insight: The Uber app is full of defects that make it difficult or impossible for blind riders to use.

Through observation and heuristic evaluation, I discovered that the Uber app was not consistently built for VoiceOver access. Logos and images were missing alt texts; the focus order of the app was not logical; some features were not available to the screen reader entirely (such as the new Safety Center). These flaws created barriers to use that was reflected in participants' experiences ordering a ride. One participant took 10 minutes to order a ride because of the barriers and confusion.

Recommendation: Fix accessibility defects. I provided a list of some that I found, with some particularly high-priority categories. A subsequent professional audit led to the remediation of over 300 accessibility defects.

Insight: The pickup is the most accutely stressful part of the journey for blind riders.

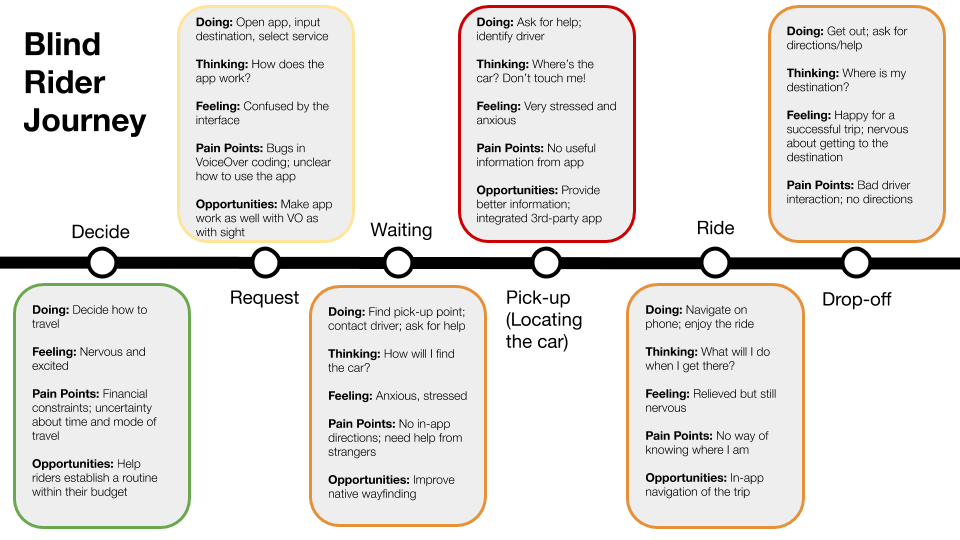

During the analysis of my research, I constructed a journey map of the non-visual rider's Uber experience. The map revealed a key point: that the pick-up is an extremely high stress moment for blind riders. The pick-up is challenging for all riders and drivers, but acutely so for blind riders, who have to find the exact right point in the physical world, the specific car they have been assigned, and do so quickly. In addition, blind riders (and riders with other disabilities) face substantial discrimination from drivers, who do not want to wait for them to find the car, or who do not want to transport a service dog (which is a legal requirement).

Conclusion: Accessibility benefits everyone

Throughout this project, I met a number of interesting, kind people who generously told me about their difficulties with transportation, Uber, and many other accessibility barriers they encounter. The recommendations I made (of which this page includes only a few) were developed firstly to improve the experiences of people with visual disabilities—to reduce and eliminate barriers that keep them from being as independent as they want.

But most of my recommendations are also rooted in principles of Inclusive Design, whose goal is to create products with enough flexibility and robustness that they can be adapted and used by anyone, regardless of ability. Make more information available in the app and you give all riders the ability to choose what they need. Smooth the pick-up through the use of multiple sensory media and you reinforce the ability of all riders to locate the right car.

This is, at its core, a project about the independence of disabled people, and the barriers transportation creates to realizing that independence. But it is also a case study of how to make things work better for everyone.